This is a repost of some critical research I performed back in 2023 that was originally hosted on Interlab's website. Since Interlab has been abandoned by it's owner and thus shut down the website, I'm posting it here to ensure the research I (solely) performed is preseved. As stated in the title, this is research from 2023 and is for archiving & indexing purposes so people can still review it.

Introduction

Since 2021, I have been closely monitoring events conducted by an advanced persistent threat group I track with Unidentified Cluster ID (UCID) – UCID902. Based on my analysis, I conclude the attempts made by this actor demonstrate continued targeting of human rights groups and activists related to advocacy of human rights in North Korea. In addition, I are continually observing this actor utilise the compromising of legitimate business websites to host their phishing kits. I believe this to be a result of either comprising of the original website developer’s infrastructure, or exploitation of the web servers themselves. I have found that the actor is a motivated, well resourced advanced persistent threat with motivations that relate closely to those demonstrated by hostile threat groups based in North Korea. The targeted threats by this group closely align with the mission of North Korea’s foreign intelligence service, Reconnaissance General Bureau (RGB). This cluster overlaps with that of ESTSecurity’s cluster which they call “Kumsong 121”.

It should be noted that there are many overlaps between UCID902 and threat group “Kimsuky” in regards to TTPs, motivations and modus operandi (MO), however, at the time of writing this, I have yet to see this activity group fall into my cluster for Kimsuky. In this report I will highlight two events from my cluster that demonstrate the activity and attack campaigns lead by UCID902.

- On 2023-03-17, I received a sample from an NGO that supports North Korean refugees. I found that this phishing campaign used a KISA Security Notification email as a lure, synonymous with historical campaigns (example: https://www.dailynk.com/20210510-3/). In addition, the phishing page mimicked that of a Naver login page, which was hosted on a legitimate Law Firm’s website, resulting in a watering hole attack. The same web server IP, hosting the Law Firm’s website, was also seen mimicking a Naver login page on 2023-01-27 on a Child Education website; which I saw involved in a targeted credential harvesting campaign against a Korean University professor. Both these sites were developed by the same developer and hosted on that developer’s webserver. The web developer was a company based in Seoul.

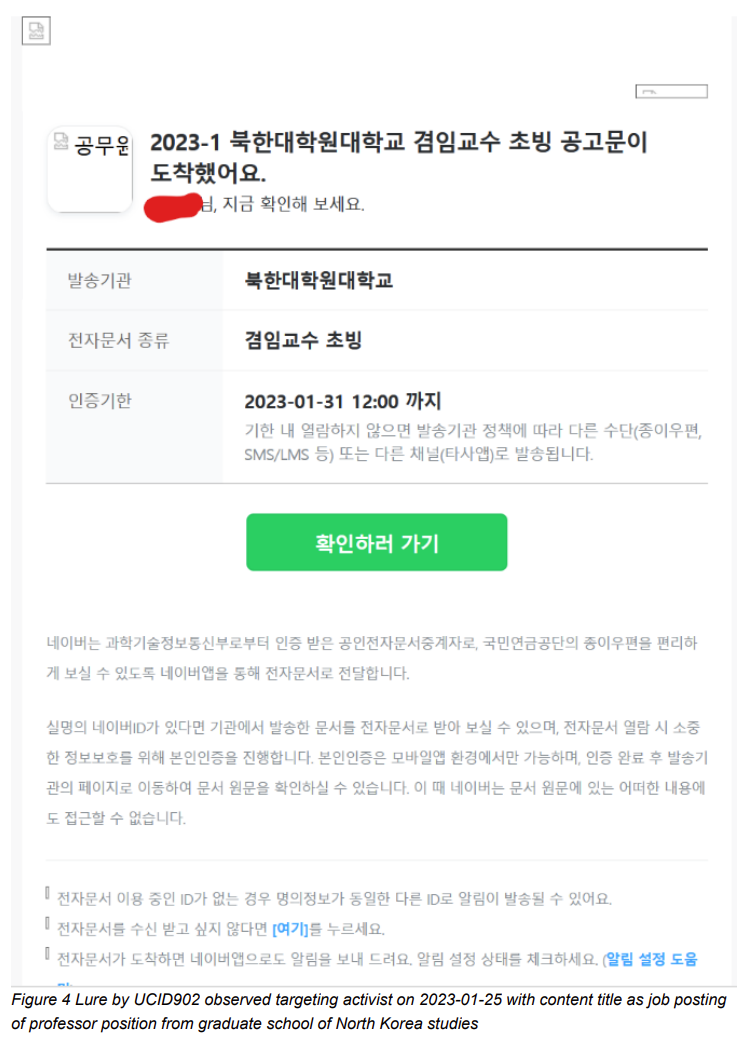

- On 2023-01-25, I received a sample from an activist based in South Korea who works on North Korean human rights. This campaign used a Naver alert message as an email lure, and directed the victim to a fake Naver login page hosted on a legitimate Medical Research Institutions website, indicating a watering hole attack. The server IP of this website was also seen on three other separate watering hole attacks I tracked. All three occasions saw credential harvesting campaigns targeting victims related to the MO of UCID902. These campaigns were also hosting Naver login pages. The websites used in the watering hole attacks described above were four differing Medical Research Institutions, which all shared the same web development company and server IP address.

Understanding UCID902’s credential harvesting operation

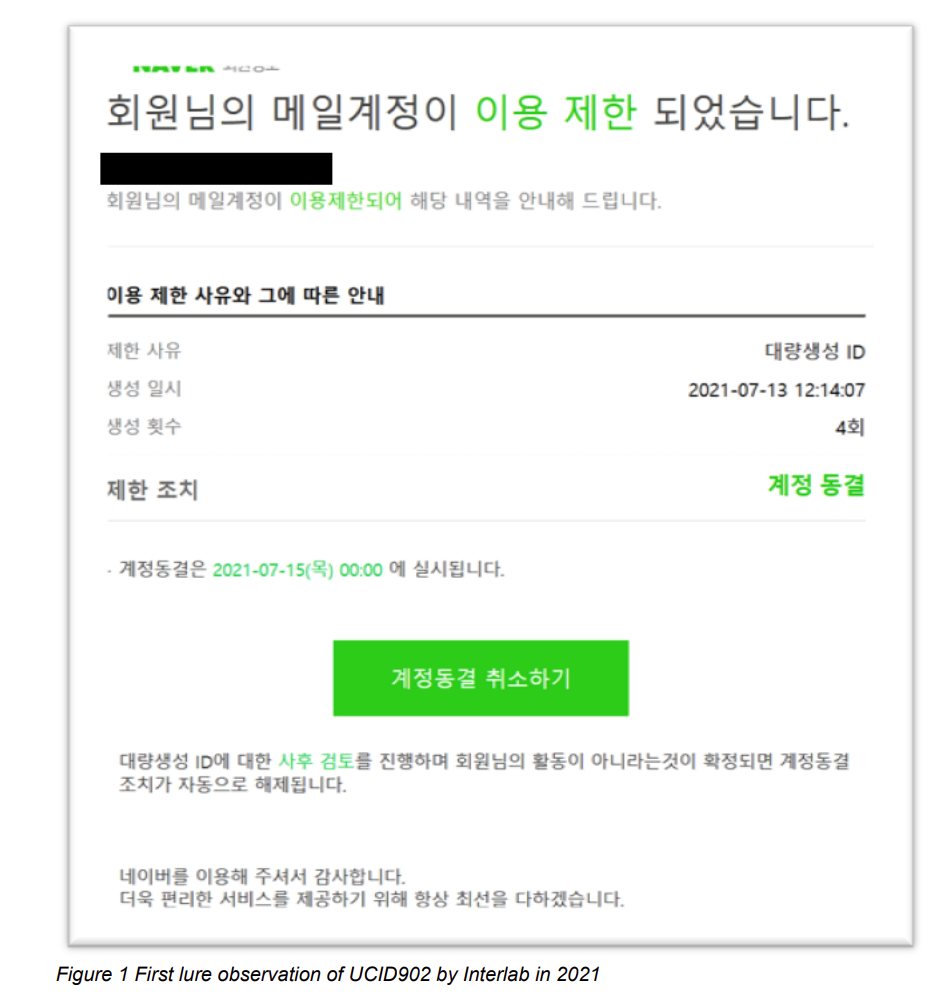

I first observed UCID902 on 2021-07-12 delivering credential phishing campaigns to activists based in the Republic of Korea. The lures aimed to appear as Naver security alerts, prompting users to input credentials, as seen in Figure 1. From 2021 to 2023, I have seen continued efforts by UCID902 to compromise credentials from victims with the same lures and phishing kits. These lures all are synonymous with Naver security events or similar.

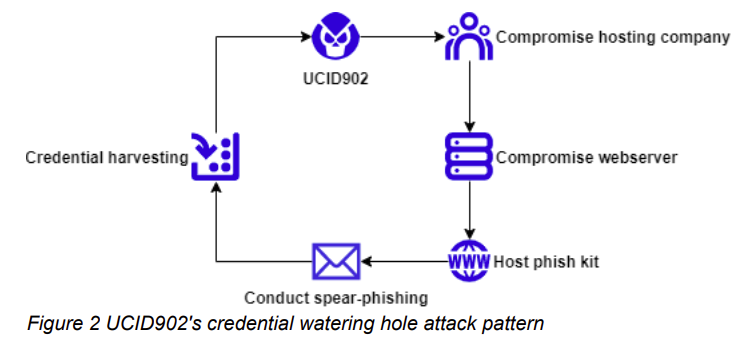

Throughout this time, I has made direct correlations within subsequent campaigns by UCID902 between events in both infrastructure (IP addresses, domains and SMTP hosts), capabilities (phishing kit) & victimology. In addition, and most notability, the actor relies heavily on watering hole attacks by compromising legitimate organisations within Korea to host phishing pages. These organisations appear to be legitimate businesses or institutions with a diverse range of industries. However, it is not the organisations themselves that relate, but the hosting provider. Throughout my tracking, I have identified many campaigns where phishing kits were hosted on legitimate company websites indicating a compromise of the website; all of these websites, within specific time windows, were hosted by the same hosting provider or hosted IP. In recent campaigns, late 2022 to early 2023, I saw constant usage of phishing kits hosted on websites built by one specific hosting provider based in Seoul, Republic of Korea. One notable characteristic of the phish kit I have observed is that it will verify that originating client has visited the page via a common user-agent and residential IP – if it doesn’t it will redirect to the legitimate Naver login page. As a result of this methodology, with medium to high confidence, I conclude that one of UCID902’s attack credential comprise methodology appears as this attack path demonstrated in Figure 2 as of 2023-03-17. I would like industry partners and governmental support to validate and understand this attack method, in order to defend the human rights ecosphere from this threat actor. Because of this, I welcome and encourage industry or governmental contribution or enrichment to this intelligence.

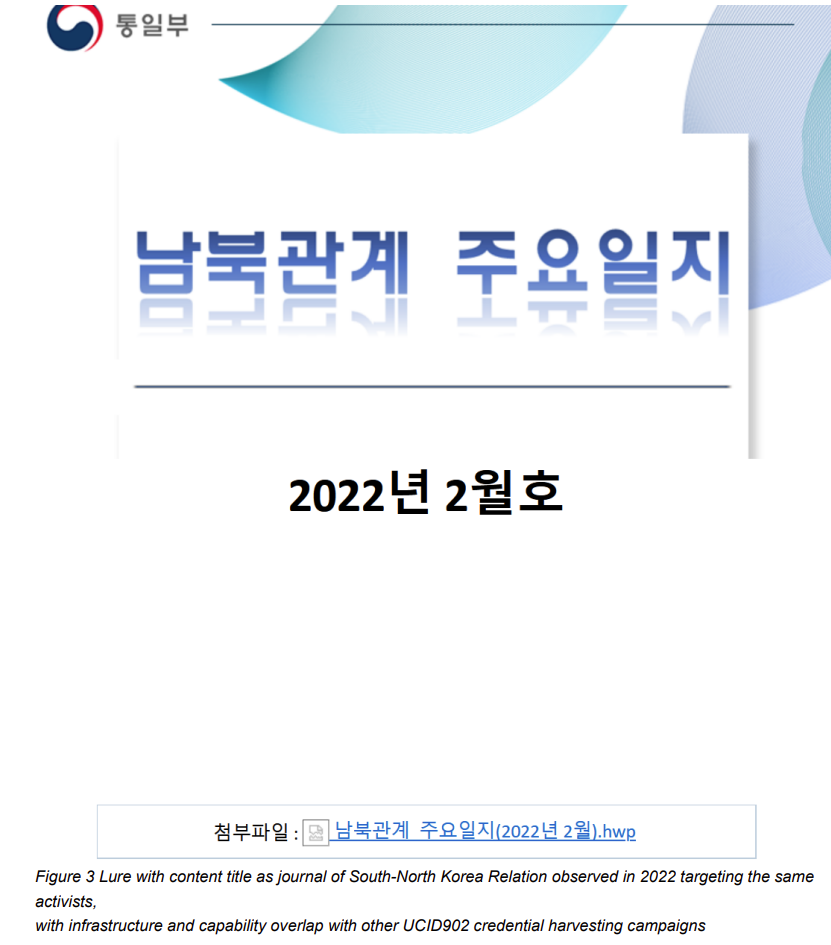

Historically, I have seen more generic campaigns targeting Naver users, to which this actor’s phish kits can often appear like. However, my first indication that this actor shares political and operational motivations as threat actors based in North Korea, began in early 2022. I observed with high confidence specific infrastructure and capability correlations with a campaign targeting activists with lures masquerading as The Ministry of Unification. This campaign included a malicious HWP document which I identified with correlations to campaigns led by APT group Kimsuky. It should be noted that this infrastructure overlap is not a common feature within my UCID902 cluster, resulting in these specific correlations being notable findings in understanding UCID902’s scope. Thus, I note that the socio-political axis of this actor closely overlaps with motivations by known threat groups based in North Korea.

Due to the infrastructure, capabilities, modus operandi, victimology and other meta-features, I believe with confidence that the threat group I classify as UCID902 are an advanced persistent threat focused on compromising credentials of activists working on North Korean human rights related activities and the unification of Korea. It should also be noted that many of the spear-phishing lures contained in campaigns led by UCID902 relate specifically to North Korean activities that would be of interest by the victims. A highly motivated actor such as this demonstrates many hallmarks of a threat group based in North Korea, however at this time I should note that I do not have 4/5 enough data points correlating to other known threat groups, such as Kimsuky, to affirm with confidence if this operation is led by them.

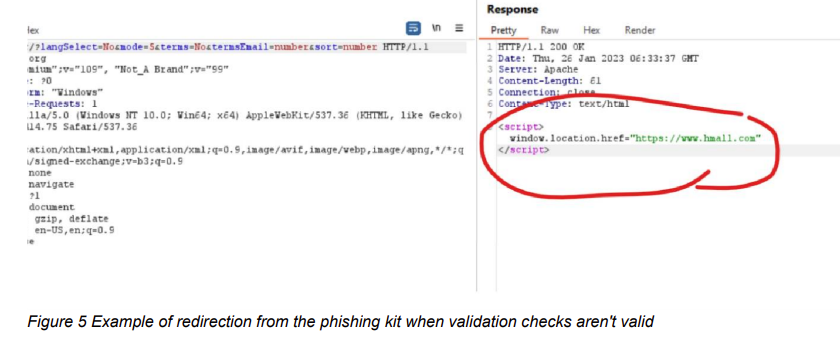

The phish kits observed in campaigns lead by UCID902 do not appear to differ throughout my observations since 2021. Across my cluster, I have indexed DOM content of all phishing sites observed in these campaigns, resulting in all of them correlating with each other. In the phishing email, the URI (contained as a link on the green button displayed in Figure 4) contains two values that determine the targeted and the redirect. I have identified a specific encoding which the actor utilises to encode the request query parameters, which I have seen throughout campaigns lead by UCID902. When the user inputs credentials on the phish kit, I note the credentials are send in a POST request back to the comprised hosting webserver. If the originating GET request doesn’t meet requirements or contain the victim identifier, the user is redirected to a different website (figure 5).

In addition, throughout campaigns lead by UCID902, email headers within the spear-phishing campaigns often showed the SMTP mail originating from the same infrastructure as the phishing kit and sender address containing a domain owned by the web development company.

Threat intelligence

I wish to share the threat intelligence I have collected on UCID902 as soon as possible to defend and help those at risk from this actor. I will do this once I have identified that the hosting companies I have reported to KISA are safely secured (At time of repost October 2024, I believe them to still be at risk). If you are part of an NGO, civil society organization or other group and believe that you have been targeted by a threat actor and wish to seek help or understand more about this targeted threat, please reach out to us. In the meantime, I will update this page with the threat intelligence I can share in due course.

Conclusion

As part of my Targeted Threats research, I will continue to monitor attack campaigns from hostile governments to human rights activists within Korea and across the globe. I believe UCID902 to be an advanced persistent threat to the human rights community in Korea and will continue to monitor and support victims of this group. I aim to support those at risk from targeted threats and share research to provide effective and actionable change to both digital security of civic organisations in Korea, East Asia and by outgrowth to global communities.

I am a security researcher working in the non-profit sector. For any inquiries regarding on this report, please reach us through Contact.

![[0x0v1]](https://www.0x0v1.com/content/images/2023/09/0x0v1-1.png)